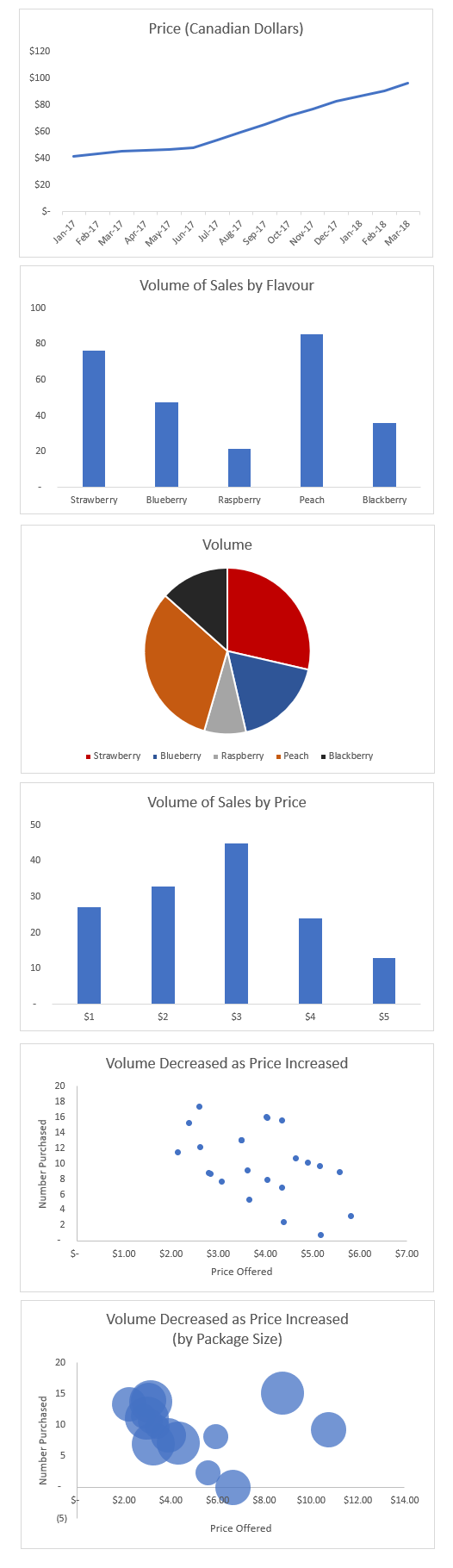

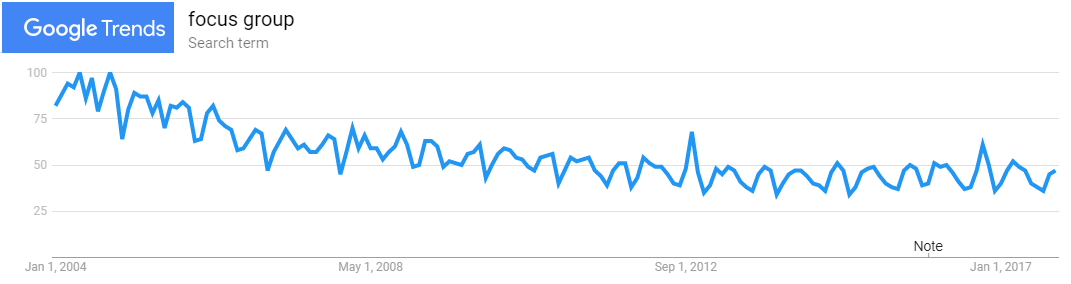

Though their use has somewhat declined given the arrival of the accessible internet, focus groups are still a very much needed tool in the market researchers toolkit. Indeed, based solely on a Google Trends chart, we’ve relied on them quite steadily for more than five years.

And as with every methodology, data quality is an important element to be carefully considered. So what happens when a researcher, or the end client behind the mirror, realizes that a participant is offering contradictory opinions? Is the participant simply lying?

And as with every methodology, data quality is an important element to be carefully considered. So what happens when a researcher, or the end client behind the mirror, realizes that a participant is offering contradictory opinions? Is the participant simply lying?

Let’s consider the possible reasons.

1) Lack of Attention. In this digital age, we’ve learned to become disinterested very quickly. But is lack of attention and interest always the participant’s fault? Moderators must first consider whether the focus group experience is sufficiently engaging and whether they ought to offer other types of stimuli that would better keep attention. On the other hand, if the participant is truly disinterested in the topic, the moderator should consider whether there was an issue with the screening questionnaire or whether the lack of interest is actually an interesting phenomenon on its own. The fact that certain people who’ve screen into a group are completely disinterested in a research topic could be an important finding on its own.

2) Misunderstandings. Language isn’t straightforward. Some words sound the same, and some words mean different things to different people. Add to that slang, idioms, and proverbs. And then also consider that some people learned the language as infants and are fluent, whereas others are still in the process of adding it to the three other languages they already know. Sometimes, it’s a wonder we can communicate at all. The moderator should be careful to ensure their language is a simple and clear as possible, and also ensure participants are easily understandable to other participants in the room.

3) Unclear questions. Often times, the questions posed are simply not specific enough. Switching among simple words can have very real consequences. For example, someone might have bought cans of soup themselves but received packets of soup from a friend and tried jars of soup at a relative’s home. It makes perfect sense for someone to have tried but never bought something (e.g., I never buy tomato sauce because my mom works at the factory and she buys it for me) just as it makes perfect sense to have bought but never tried something (e.g., I really don’t care for mushrooms but I buy them all the time for my family members). Moderators need to parse out which details could be causing discrepancies.

4) Changed their mind. Have you ever bought something and then regretted it? Or not bought something and regretted it? People are irrational and regularly change their minds or recall things moments later. Take note of which comments or questions might have triggered that change of mind or sudden recall. Changing your mind isn’t an error. It’s a demonstration of thought processes that could also happen during the purchase cycle. That change of mind could even be a very important insight.

5) Reaction to other opinions. If you partake in social media, you’ll see many examples where someone states a position and then changes their stance upon reading the host of responses that immediately result – “I didn’t think about it that way.” Similarly, in a focus group, where six to ten people from completely different backgrounds and experiences bring their own situations to the mix, people may hear a wide range of never-before considered opinions that cause them to change their own opinion. Learn from this. Try to identify which opinions were most impactful and how you might be able to use them.

6) Response Effects and Bias. People are irrational. We want to give answers that please other people, we don’t want to offend others and so avoid sharing our real opinions, we choose to believe what people say before we check the facts. We know of hundreds of human biases and there are likely hundreds more we’ve yet to identify. Every one of these biases is hard at work trying to get its way during every focus group. The best a moderator can do is be aware that those biases are there and try to recognize when the bias has taken control. And of course, take note of which bias is at play so that that brand can examine it more carefully.

7) Lying. And yes, naturally, someone might simply be lying. It’s a rare occurrence but it can happen. If you’ve managed to rule out all of the previous options, then you might simply have to ask someone to discontinue their participation. Because data quality matters.

You might like to read these: