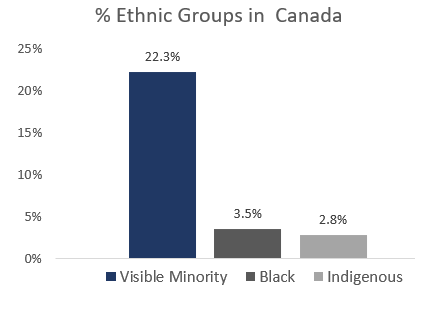

From a land solely populated by indigenous peoples, the last five hundred or so years brought an influx of people from all over the world to what is now Canada. According to 2016 census data, about 22% of people in Canada are visible minorities including about about 2.8% who are indigenous, and about 3.5% who are Black.

From a land solely populated by indigenous peoples, the last five hundred or so years brought an influx of people from all over the world to what is now Canada. According to 2016 census data, about 22% of people in Canada are visible minorities including about about 2.8% who are indigenous, and about 3.5% who are Black.

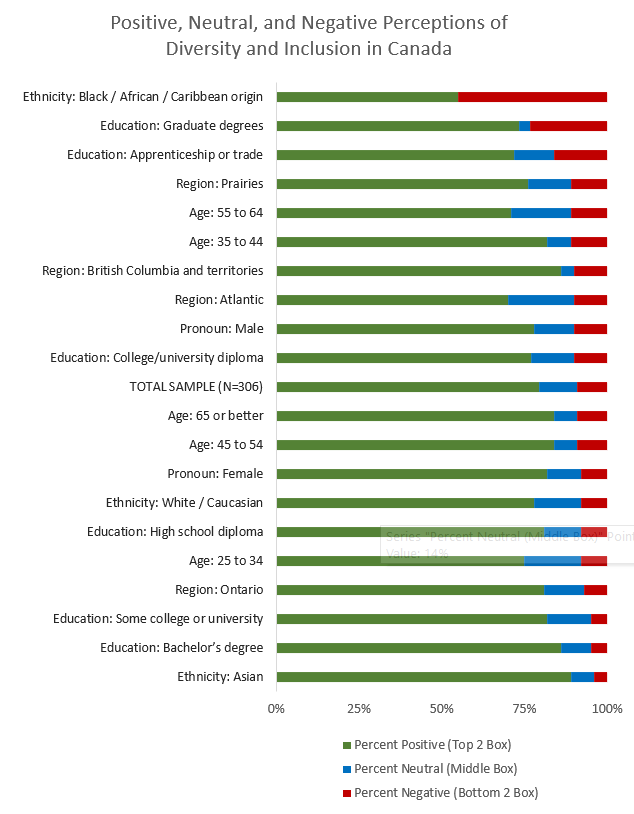

In recent weeks, conversations of diversity, inclusion, and equity for Black and indigenous people in particular have entered boardrooms in a big way. It’s no different in the research world. We’ve had discussions about diversity within our team, and we’ve done research on how Canadians feel about diversity.

But diversity is a key issue for our research processes as well. Here are four things your research team can do to help improve the quality of data and ensure the resulting generalizations are more inclusive.

Boost sample sizes.

Many of us have a favourite sample size that we rely on. It might be 300, which gives us a margin of error of about 6 percentage points, or 500 which gives us a margin of error of about 5 percentage points. However, a sample of only 300 Canadians means that only 9 indigenous people (2.8%) and 10 Black people (3.5%) would be included in the research.

These numbers are far too small to make any valid and reliable generalizations about the products and services they might need, and whether their needs are the same or different from the average person. In fact, investigating these segments in depth is often summarily dismissed because the sample sizes are too small. That’s not a pathway to increasing equity in society.

As such, researchers should make concerted efforts to boost sample sizes for Black and indigenous people, at least up to 30 people each and preferably up to 50 people each. This will help identify whether there are any differential results and whether those results are potentially actionable.

Prior to analyzing the total population, be sure to weight the boosted segments back down to their original percentages based on the original sample size. Thus, if the GenPop sample is 300 and indigenous people were boosted from 9 people to 30 people, retain 300 as the sample size and weight indigenous people back down to 2.8% of the sample.

Mirror the geographic area.

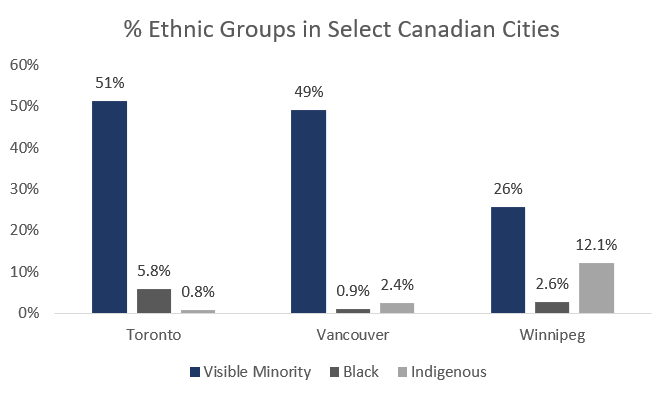

Take full advantage of national census statistics. Our census data indicate that although 2.8% of people in Canada are indigenous, this percentage rises to 12% in Winnipeg and is only 0.8% in Toronto. Similarly, though 3.5% of people in Canada are Black, this percentage decreases to 0.9% in Vancouver and rises to 5.8% in Toronto. If the research objectives focus on a specific region of Canada, ensure that the sample demographics mirror those regions with the addition of booster samples.Because of lower research response rates from Black and indigenous people, you may need to increase field lengths to achieve full representation. But studies that stay in field long enough will benefit from a more diverse group of participants.

Take full advantage of national census statistics. Our census data indicate that although 2.8% of people in Canada are indigenous, this percentage rises to 12% in Winnipeg and is only 0.8% in Toronto. Similarly, though 3.5% of people in Canada are Black, this percentage decreases to 0.9% in Vancouver and rises to 5.8% in Toronto. If the research objectives focus on a specific region of Canada, ensure that the sample demographics mirror those regions with the addition of booster samples.Because of lower research response rates from Black and indigenous people, you may need to increase field lengths to achieve full representation. But studies that stay in field long enough will benefit from a more diverse group of participants.

Identify key segments.

Prior to going into field, do secondary or desk-top research to identify whether your topic is of particular relevance or interest to Black or indigenous people. Are they the trend setters? Are they more likely to use or benefit from your product or service? Are they likely to discover or use your product/service in a very different way than other segments of the population? If you intentionally plan your research by anticipating differential needs, perceptions, emotions, and actions from various groups of people, you can create a research tool that incorporates more inclusive content.

Eliminate micro-aggressions.

Micro-aggressions, presumptions about people based on stereotypes, can be hard to spot when you’re rarely on the receiving end and sometimes on the dispensing side. They’re sometimes offered as back-handed complements like “I can hardly hear your accent” or “You’re so articulate,” the assumption being that an accent different from yours is a negative thing or that you didn’t expect they could be articulate. Micro-aggressions are often referred to as death by a thousand cuts – one micro-aggression is manageable but reading multiple aggressions throughout a long questionnaire is painful. And completion rates suffer.

Geography: A common micro-aggression that has been well-documented with humour is the ”Where are you really from” question. The problem with this statement is it presumes BIPOC people (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) don’t come from Canada even if they were born here, and even if their parents and grandparents were born here. Regardless of someone’s ethnicity or name, if they say they are from Halifax or Kuujjuaq, then that’s where they’re from.In the research world, take care to ask origin, ethnicity, or culture questions respectfully. Think about whether you must know if a person was born in Canada, if they were raised in Canada since they were a toddler, or how long any household members had lived in the region during the time the person was raised. Culture is learned from family, friends, neighbours, and media, and cannot be inferred from recoding names or ethnicities provided in a questionnaire.

Language: Similarly, don’t make stereotypical assumptions about language based on names, ethnicities, or geography. Given Canada’s diverse cultures, someone could easily be multi-lingual and not speak English. They might, in fact, speak French, Inuktitut, and Dene. We know that French speakers live in British Columbia and Ojibway speakers could live in Halifax. Ensure that any questions about language reflect the diversity of Canada. Even better, translate questionnaires into the key languages of each area where the research will take place. Again, national census data is a great source of information.

.

Sex and gender: Don’t make assumptions about sex and gender. Stereotypes like policeman, housewife, stay-at-home mom, and Chairman are no longer appropriate. In fact, there are often better words that are inherently more inclusive: police officer, homemaker, caregiver, and Chair. Seek out gendered words, including he and she, and replace them with more inclusive options like ‘they’. Similarly, husband and wife can be exchanged for spouse or partner, and brother and sister can be exchanged for sibling.

Reading skills: Seek out idioms, metaphors, and similes in questionnaires and individual interviews. In many cases, eliminating these words and phrases not only makes it easier to read for people who don’t have English as a first language, it also eliminates many words that have sexist, racist, homophobic, and ableist histories.

Unless you’re using them in the precise situation for which they’re intended, avoid offering descriptor words like: dumb, lame, stupid, crazy, insane, mad, nuts, invalid. Also to be avoided are phrases like: cake walk, ghetto, grandfathered, hooligan, master/slave, and paddy wagon. If a question needs to use one of these words, think about what the real intention of the question is and use those words instead. Thus, instead of asking people to choose one of those less effective words to describe a company, give them words like: easy, poor quality, experienced, inexperienced, ignorant, disorganized, complicated. A quick internet search will get you started.

More than half of our team members are visible minorities and we’d love to help you create research that is more inclusive. Please get in touch with us!

.

You might like to read these: